- ASPLOS 2020

- Paper

- Soruce Code

Intel SGX is a hardware-based trusted execution environment (TEE), which enables an application to compute on confidential data in a secure enclave. SGX assumes a powerful threat model, in which only the CPU itself is trusted; anything else is untrusted, including the memory, firmware, system software, etc. An enclave interacts with its host application through an exposed, enclave-specific, (usually) bi-directional interface. This interface is the main attack surface of the enclave. The attacker can invoke the interface in any order and inputs. It is thus imperative to secure it through careful design and defensive programming.

In this work, we systematically analyze the attack models against the enclave untrusted interfaces and summarized them into the COIN attacks -- Concurrent, Order, Inputs, and Nested. Together, these four models allow the attacker to invoke the enclave interface in any order with arbitrary inputs, including from multiple threads. We then build an extensible framework to test an enclave in the presence of COIN attacks with instruction emulation and concolic execution. We evaluated ten popular open-source SGX projects using eight vulnerability detection policies that cover information leaks, control-flow hijackings, and memory vulnerabilities. We found 52 vulnerabilities. In one case, we discovered an information leak that could reliably dump the entire enclave memory by manipulating the inputs. Our evaluation highlights the necessity of extensively testing an enclave before its deployment.

Target

To find vulnerabilities of SGX applications in four models:

- Concurrent calls: multithread, race condition, improper lock...

- Order: assumes the calling sequence

- Input manipulation: bad OCALL return val & ECALL arguments

- Nested calls: calling OCALL that invokes ECALL, not implemented

Design & Method

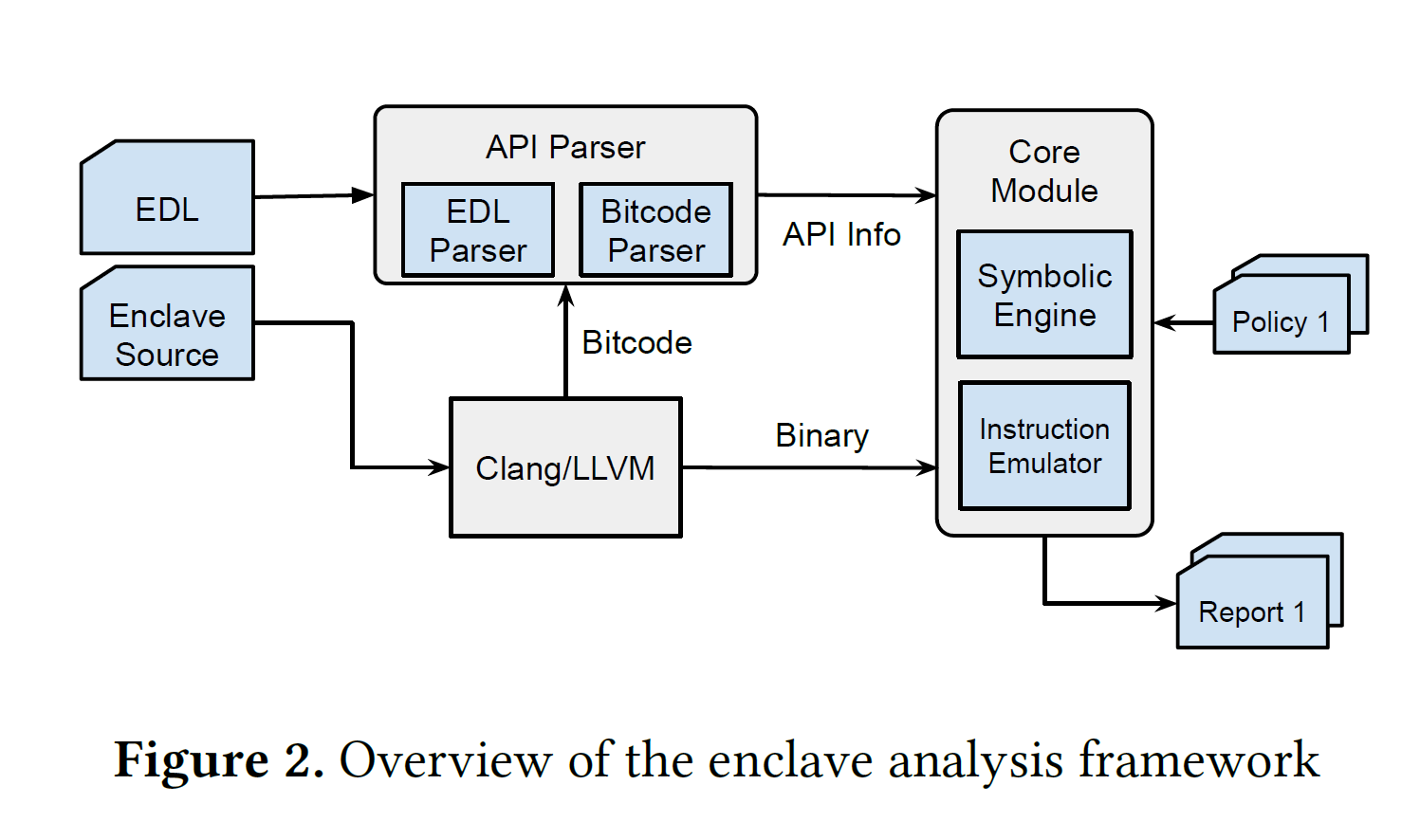

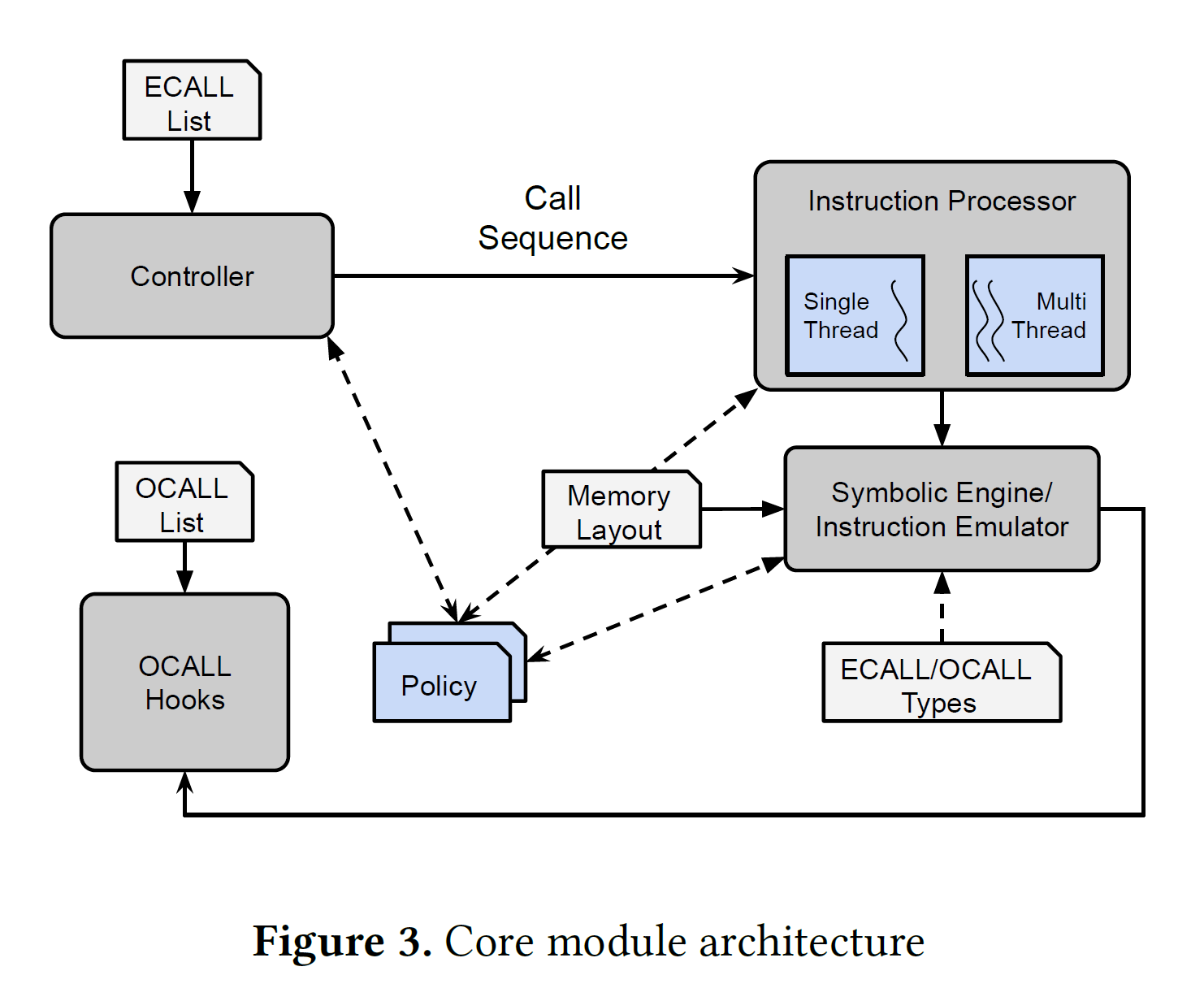

The design of COIN:

- Emulation: QEMU

- Symbolic execution: Triton (backed by z3)

- Policy-based vulnerability discovery

Results

COIN uses 8 policies to find the potential vulnerabilities:

- Heap info leak

- Stack info leak

- Ineffectual condition

- Use after free

- Double free

- Stack overflow

- Heap overflow

- Null pointer dereference

COIN Attack

- ASPLOS 2020

- Paper

- Soruce Code

Target

- Emulate TrustZone OSes(TZOS) and Trusted Applications (TAs)

- Abstract and reimplement a subset of hardware/software interfaces

- Fuzz these components

- TZOSes: QSEE, Huawei, OPTEE, Kinibi, TEEGRIS(Samsung) & TAs

Results

COIN uses 8 policies to find the potential vulnerabilities:

- Heap info leak

- Stack info leak

- Ineffectual condition

- Use after free

- Double free

- Stack overflow

- Heap overflow

- Null pointer dereference

Review

Strength

- Symbolic execution + emulation

- Policies can be configurable

- Real world problems

- Solid work

- Efforts taken to run TZOS and TA in emulation environment

- Acceptable performance

Weakness

- nested call left unimplemented

- May not be powerful enough to deal with complicate situations

- Policies are mainly at relatively low-level

- Low coverage

- Crashes -X-> vulnerabilities

PartEmu

- USENIX Security 2020

- Paper

- Source code unavailable

Traditional TrustZone OSes and Applications is not easy to fuzz because they cannot be instrumented or modified easily in the original hardware environment. So to emulate them for fuzzing purpose.

Design & Method

- Re-host the TZOS frimware

- Choose the components to reuse/emulate carefully

- Bootloader

- Secure Monitor

- TEE driver and TEE userspace

- MMIO registers (easy to emulate)

Tools

- TriforceAFL + QEMU

- Manually written Interfaces

Results

Emulations works well. For upgraded TZOSes, only a few efforts are needed for compatibility.

TAs

Challenges

- Identifying the fuzzed target

- Result stability (migrate to hardware, reproducibility)

- Randomness

| Class | Vulnerability Types | Crashes |

|---|---|---|

| Availability | Null-pointer dereferences | 9 |

| Insufficient shared memory crashes | 10 | |

| Other | 8 | |

| Confidentiality | Read from attacker-controlled pointer to shared memory | 8 |

| Read from attacker-controlled | 0 | |

| OOB buffer length to shared memory | ||

| Integrity | Write to secure memory using attacker-controlled pointer | 11 |

| Write to secure memory using | 2 | |

| attacker-controlled OOB buffer length |

Just like the previous paper, the main causes of the crashes can be attributed to:

- Assumptions of Normal-World Call Sequence

- Unvalidated Pointers from Normal World

- Unvalidated Types

TZOSes

- Normal-World Checks

- Assumptions of Normal-World Call Sequence